By Julie Somers

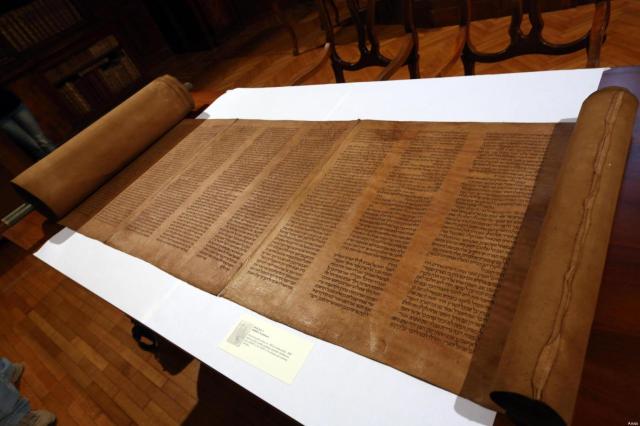

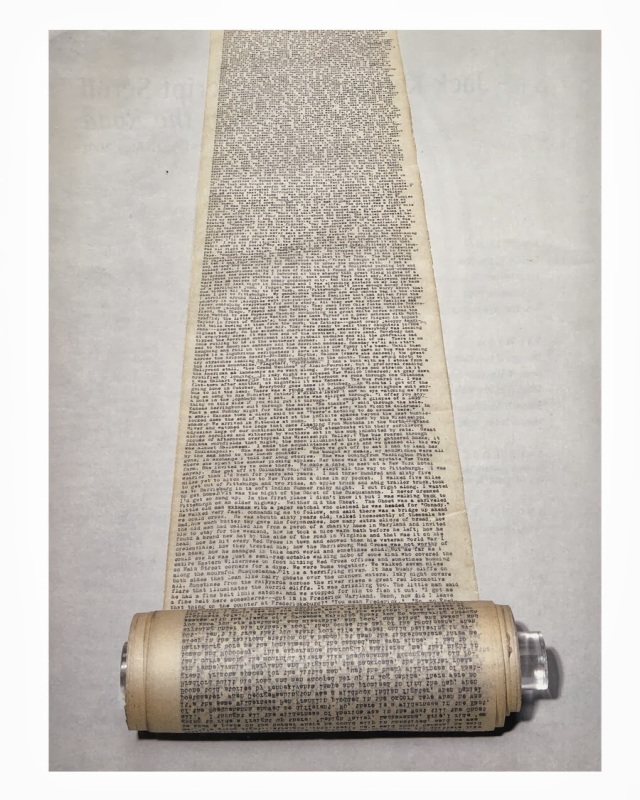

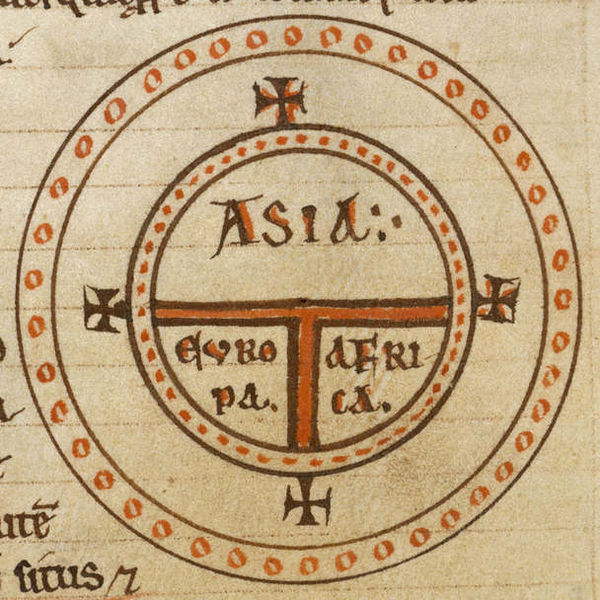

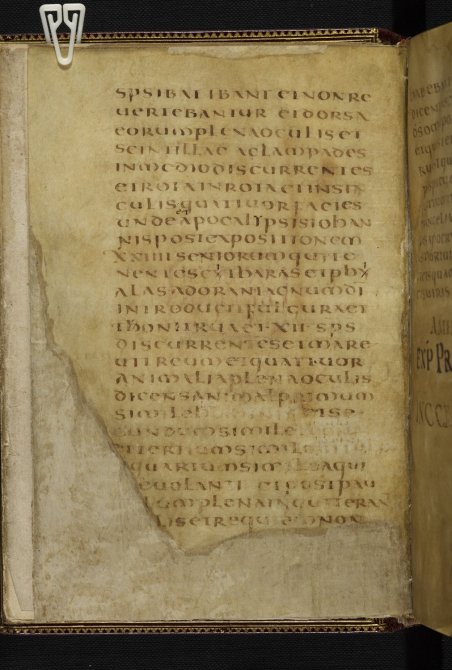

My colleagues and I at the Turning Over a New Leaf Project spend a lot of time thinking, talking, and reading about, well, reading. More specifically, we question the various forms of reading, as well as the ways books were used in the Middle Ages. Recently we discussed the interplay of script and image, which made me think of the banderole (Fr. “little banner”), which is essentially the medieval speech bubble. Sometimes referred to as angel banners, phylactère or speech scrolls, banderoles were employed by medieval artists and scribes as a visual way of conveying spoken words. Different from tituli, which provided more of a summary title or caption for an image, the banderole points to an interaction within an image, as well as encouraging the reader to imagine a conversation, thus requiring the reader to ‘listen to the text’.[1] S-shaped scrolls or ribbons of words that seem to unfurl from the mouths of the speakers add an element of sound to the images. Banderoles are inscribed with words that suggest a conversation, with the direction the scroll unrolls possibly indicating the direction of speech.

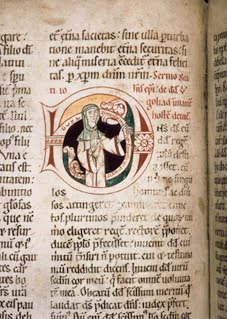

Gospel Book of Henry the Lion. 12th. c. Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2° Der Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel

Banderoles are often carried by the speaker; they are pictured holding their words and thus owning their voice. This is evident in the example below from a twelfth-century Psalter where the nun-scribe holds in her hand a banderole inscribed, ‘Guda peccatrix mulier scripsit et pinxit hoc librum’ (Guda a sinner wrote and painted this book).

Some banderoles remain empty. We must imagine the conversation between this friar and Beguine, who have been left with nothing to say at all.

Banderoles could also indicate singing or a multitude of voices. Though the text is silent, the sound resides in the mind of the reader.

Throughout the high and later Middle Ages the banderole was an increasingly popular motif used in various media, including sculpture, manuscripts, stained glass, tapestries and paintings.

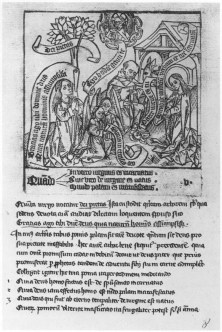

The tradition continued into the era of printed books where banderoles figure prominently in woodcut illustrations.

Detail from ‘Fortune and Death’ by the Master of the Banderoles, c.1450-1475

showing a banderole or scroll containing ‘speech’ text emanating from the King

In fact, by the mid-fifteenth century the ‘Master of the Banderoles’ (Meister mit den Bandrollen) was one of the earliest professional printers in the Netherlands.[2]

This last image is a photo I took in the Chapel of Tears (Chapelle des Larmes) at Mount Sainte-Odile in Alsace, France. It is a beautiful 20th century mosaic that uses the medieval motif of banderoles to convey a sense of conversation, with the scrolls emanating from the center to the periphery in a back and forth motion between the figures.

As we are all familiar with the speech bubble as it is used in comic books today, banderoles continue to fulfill the same function of connecting words with image, making the reader ‘listen’ to the text.

[1] Paul Saenger. Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford University Press, 1987. p. 187

[2]http://www.europeana.eu/portal/record/08501/4A5903F1491D7C25F9F327EB399EC8AE82707AF6.html http://www.wopc.co.uk/netherlands/master-of-the-banderoles.html

![A punctus elevatus sitting snugly between a [t] and an ampersand in BM Cambrai 215, f. 128](https://medievalfragments.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/bm-cambrai-2152c-f-128.jpg?w=237&h=104)