Our blog has featured medieval bindings before (Jenny’s blog on “bling” bindings was recently published in Quest magazine) but with an eye to the extraordinary, and extremely rare. In fact, finding an intact medieval binding, never mind a beautiful one, is not particularly common. Whether replaced in response to wear and tear or to update the book’s appearance, most manuscripts encountered by the researcher won’t arrive in their original bindings. Because of this, many manuscript scholars are unable to ‘judge a book by its cover’ (or, more fairly, judge it alongside its cover) in their research, and the topic of medieval bindings is therefore overlooked. My research corpus includes a number of manuscripts in original medieval bindings, discussed below, which makes them even more interesting to me!

What do normal, more workaday manuscript bindings actually look like? Well, as with all things manuscript related, it depends on a multitude of factors.

Parts of a manuscript binding. From Michelle Brown, Understanding Illuminated Manuscripts: A Guide to Technical Terms (London: The J. Paul Getty Museum in association with the British Library, 1994), 7. See the BL’s online glossary.

The shift from roll to codex meant a fundamental change in the physical format in which one accessed texts. The new codex was much easier to store, transport, and reference, with its own built-in connection and protection structure – its binding. While the codex was ubiquitous in the west from the 5th century onwards, the oldest extant western binding encloses the St Cuthbert Gospels, c. 700.

The St Cuthbert Gospels, front cover, dyed-red goat skin with tooling. Photo by British Library; see the full manuscript at the British Library website.

The earliest books were likely bound using the Coptic method (which you can learn to do yourself). While easy to make and flexible, this type of binding is not very durable. The Carolingians developed a sturdier style characterized by raised bands (or ribs) along the spine and heavy flat boards (see a tutorial here).

St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 175. 9th century binding, front and spine. Photos by e-codices, where you can view the entire manuscript.

As you can see, these simple bindings aren’t as glamorous as contemporary treasure bindings, such as the Codex Aureus of St Emmeram. They did the trick however, aesthetically and functionally. This binding method generally persisted for several more centuries, with some variations in the way quires were sewn to the ribs, and the methods by which the boards were attached to the spine. At one point seemingly dull bindings like these may have had now-lost furnishings like bosses (metal studs meant to hold the leather covers off the surface it rested on to protect it), clasps, dye, or even stamps or tooling, like this Romanesque binding at the British Library.

British Library, Egerton MS 272, c. 1225, from the priory of St Mary Overy in Southwark.

Later medieval libraries sometimes attached chains to the back covers of their books to keep them in place; see Jenny’s blog on chained libraries and the Project’s visit to Zutphen.

As mentioned above, and briefly discussed in a past blog, a good number of the manuscripts I work with from Ten Duinen, an abbey formerly on the West-Flemish coast, are encased in medieval bindings. (I encourage Dutch speakers to read the Bruges Public Library’s blog about them. The Library is unique and indeed blessed to have a truly impressive collection of medieval bindings.) Although there is some variety in my corpus, I do have a favourite type: their in-house, late 12th/early 13th century Cistercian-style bindings.

Bruges, Bruges Public Library, Ms 27; spine and front. (As indicated by my arm and hand on the left, this is a hefty volume!) Photo Jenneka Janzen.

In one example, Ms 27, the boards (according to the Bruges Public Library, oak) are covered in brown leather. The outer front cover shows, at the corners and centre, marks where the metal bosses were attached. The ribs along the spine are not as prominent as in other examples, although you can see one exposed cord at the tail end.

From the inside, you can see that the channeling, cords, and sewing stations are exposed. The back pastedown, now lifted, was taken from a 12th century Ritual (medieval bindings very often contain fragments of ‘recycled’ books). Neat, isn’t it?

Well, the back cover, shown above, is even better. Here you can see a small (14th century) fenestra of metal and transparent horn holding the title of the book. (Holes from an earlier fenestra lie above it.) There are also, painted in black ink, a large G and smaller C; these were likely used by the librarian to classify and maybe shelve the book. Other manuscript bindings in my corpus have leftover bits of clasps or chains, and even 800 year-old cow hair (which is now an interesting shade of green). Generally, medieval bindings are covered in cow, pig, sheep, or goat leather, with the hair scraped off. Not so here!

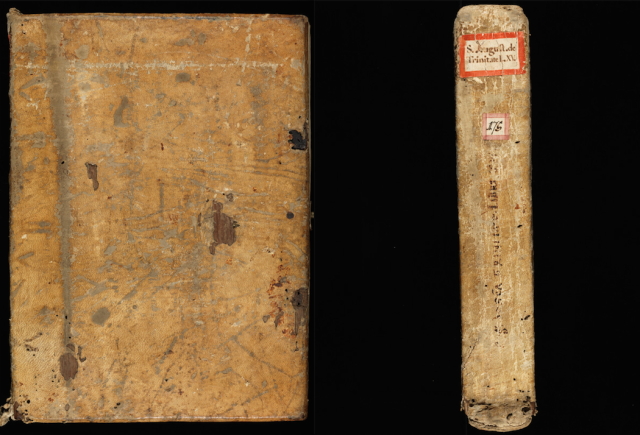

Medieval bindings are such a fascinating and deep study area that what I’ve shared here is a drop in the ocean. Limp or parchment bindings, girdle books, and chemise bindings warrant their own entries, as do in-depth looks at the processes, regional variations, and chronological developments of bookbinding. Online stamp and tooling identification engines, bookbinding databases, and issues of conservation may also appeal to binding aficionados.

For much more on bindings, start with J.A. Szirmai’s authoritative The Archaeology of Medieval Bookbinding. For binding eye candy, sites like the British Library’s Databank of Bookbindings, the National Library of the Netherlands’ Dutch Bindings digital collection, and the Schøyen Collection‘s bindings site are great places to start!

(With thanks to the Bruges Public Library for allowing me to post my research images.)