By Jenny Weston

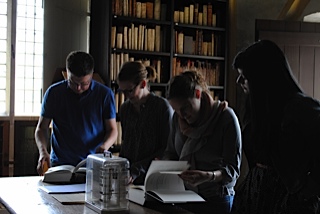

On a beautiful sunny day last week, the Turning Over a New Leaf project team decided to take a day off from the office to visit a spectacular chained library in the small town of Zutphen (located in the eastern part of the Netherlands). Built in 1564 as part of the church of St Walburga, it is one of only five chained libraries in the world that survive ‘intact’—that is, complete with the original books, chains, rods, and furniture.

Needless to say, it was a rather surreal moment for all of us to step into the little room to see the dark-wood lecterns, upon which were placed (in neat rows, side-by-side) beautiful 15th- and 16th-century books, secured in place by metal chains.

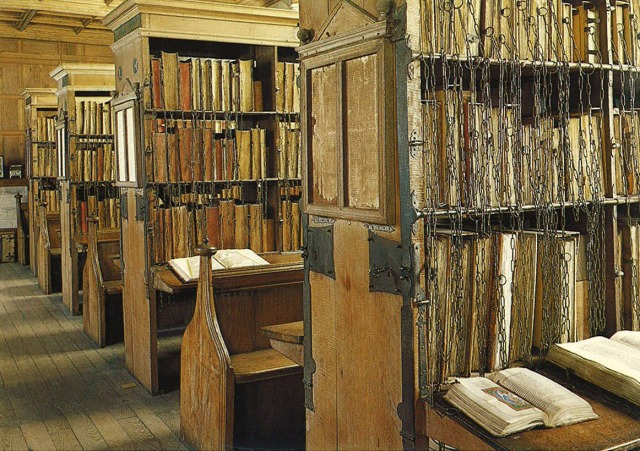

Looking closer, it is possible to see just how the chained-library system works. Each book is fitted with a metal clasp, usually on the back cover, and then a metal chain is attached and strung through a long metal rod. The rod is then locked in place either to a lectern (or to a bookcase, depending on the library).

During the later middle ages, more and more people were interested in reading, and chained libraries provided an excellent resource for those who could not afford to purchase books themselves. The system of locking the books to the room, thus allowed the public free access to read, while at the same time safe-guarding the library’s valuable collection from potential thieves.

(For more photos of Zutphen, see Erik Kwakkel’s recent Tumblr post).

Perhaps one of the world’s most famous examples of a chained library is that of Hereford Cathedral in England. Constructed in the early 17th century, it is one of the largest surviving examples of a chained library with over 220 manuscripts (including the famous eighth-century Hereford Gospels).

The layout of this library differs slightly from Zutphen, as the books are chained to a bookcase, as opposed to a lectern. Although the view might have been ‘less-than-inspiring’, the reader could choose from a wider number of books.

What I find especially neat (and slightly terrifying) is the effect of the chains dangling down in front of the books—almost like some scary metal veil. (I wonder how many readers have experienced book-themed nightmares after visiting this library).

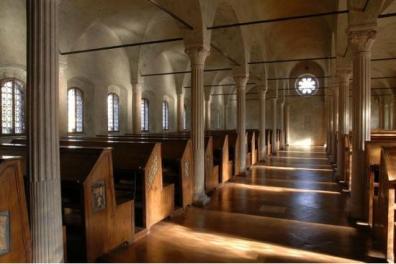

I would like to also briefly mention the beautiful Malatestiana Library in Cesena, Italy. This library was commissioned and constructed between 1447 and 1452 by the Lord of Cesena (Malestesta Novello) who wished to have a public space for reading. The library was attributed to the Friars of St. Francis and its construction greatly added to the library’s original collection—expanding it from 50 books to over 340.

The library is designed almost like a church with pews where readers could sit and read. The books are tucked inside the small lecterns in front:

Recently, the library’s collection has been documented by the ‘Open Catalogue of the Malastestiana Library‘ project, which is now available online (with lots of manuscript images)!

What I find so interesting about the chained library is the rather fascinating dichotomy between the idea of ‘locking the books down’ in order to create a free, open, and shared space for an entire community to engage in reading. Despite the slight air of ‘mistrust’ (in a perfect book utopia, chains would not be needed), there is still a strong sense of community that underlines the creation of such libraries.

In Zutphen, for example, sixty keys to the front door of the library were issued, not only to the canons, but also to the townspeople—creating easier access to the books. The Malaestiana Library was also the dream of a nobleman, who wished to build a library open for everyone, and keys to the library were given to both the monks, as well as town officials.

So despite the rather austere measures enacted to prevent book-theft, these chained libraries were very much the product of a collective desire to share books with the entire community—truly the world’s first public libraries.