We’ve been blogging at MedievalFragments for nearly two-and-a-half years, but like all good things, it has to come to an end sometime! The project, Turning Over a New Leaf, is coming, in part, to a conclusion, with two of its members completing their contracts at Leiden University. So, in farewell, we’re taking this opportunity to review our years of blogging…

Some stats:

– We’ve written 130 posts since the launch of the blog on February 25, 2012 (this will be our 131st post!)

– We’ve had nearly 250,000 views (249,032 to be precise, as of 10am this morning)

– Our best ever day of views (over 6000) was Tuesday April 2, 2013 – thanks to one of our posts (guest written by Thijs Porck, lecturer at Leiden University) going viral on Reddit. You can read ‘Paws, Pee and Mice: Cats Among Medieval Manuscripts’, one of our top performing blogs, here. It’s had over 60,000 views to date!

– Our readers climbed from around 18,500 in our first half year of blogging (2012), to over 133,000 in 2013… proving, perhaps, that persistence in academic blogging pays off.

We’ve used the blog for a variety of purposes, including publicising the project, writing about our research, and about conferences and exhibitions we have attended. Most of all, we’ve enjoyed writing the blog as a way to encourage knowledge of medieval manuscripts. Some of our posts have found a broader audience, such as Jenny Weston’s post on Manuscripts for the Rich & Famous (Super Bling)!, which was picked up and reprinted by Quest Magazine, a history magazine for children available on the iPad. We hope that the blog will continue to be useful for teachers and students of medieval history, and for anyone who loves medieval manuscripts like we do!

What next? The project will officially come to an end in May 2015. Future activities include a conference to be held in March 2015 (‘The European Book in the Long Twelfth Century’ – you can watch for updates on this and other events on our homepage). We will also continue to maintain and update our Flickr and Facebook pages. Erik Kwakkel, project leader, has recently started a new blog, and continues to maintain a lively Twitter and Tumblr stream. He continues his research on dating medieval script, and has a number of publications in progress. Irene O’Daly, postdoc on the project, is starting a new position as Research Associate at the John Rylands Research Institute at the University of Manchester. She’s writing a book on ‘Diagrams and the Study of Ciceronian Rhetoric in the Middle Ages’. Jenny Weston, PhD student, is finishing her thesis on ‘Devotional Reading at the Abbey of Fécamp, c. 1000-1200’, and hopes to defend in early 2015. Julie Somers, PhD student, will continue work on her thesis ‘Women and the Written Word: Textual Culture in Court and Convent During the Twelfth Century Renaissance’. You can follow her on Twitter, and check out beautiful photos of all things medieval on her personal Flickr stream, and her Tumblr. Jenneka Janzen, PhD student, is also working on a thesis-in-progress on ‘Written Culture at Ter Duinen: Cistercian Monks and their Books, 1140-1250’, and will be exploring the treasures of libraries in Bruges further over the course of the next year. She is also an Editor in Chief of the Journal of the LUCAS Graduate Conference, issues of which can be downloaded here.

We’d like to take this opportunity to offer some thanks. The project has been funded by the NWO (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek), and we have been very grateful for its support. We’d like to thank Leiden University, particularly the Special Collections section at the University Library, for allowing generous access to their manuscript collection. We’ve had a number of guest bloggers over the duration of the blog, and have really appreciated their contribution: Thijs Porck, David Ganz, Francis Newton, Ramona Venema, Marjolein de Vos, Cynthia Lange, and Giulio Menna. Finally, we are thankful to all the readers of the blog – we hope you have enjoyed our posts as much as we have enjoyed writing them!

P.S. We have a not-so-secret plan in the works to publish some of our blog posts in a book – stay tuned!

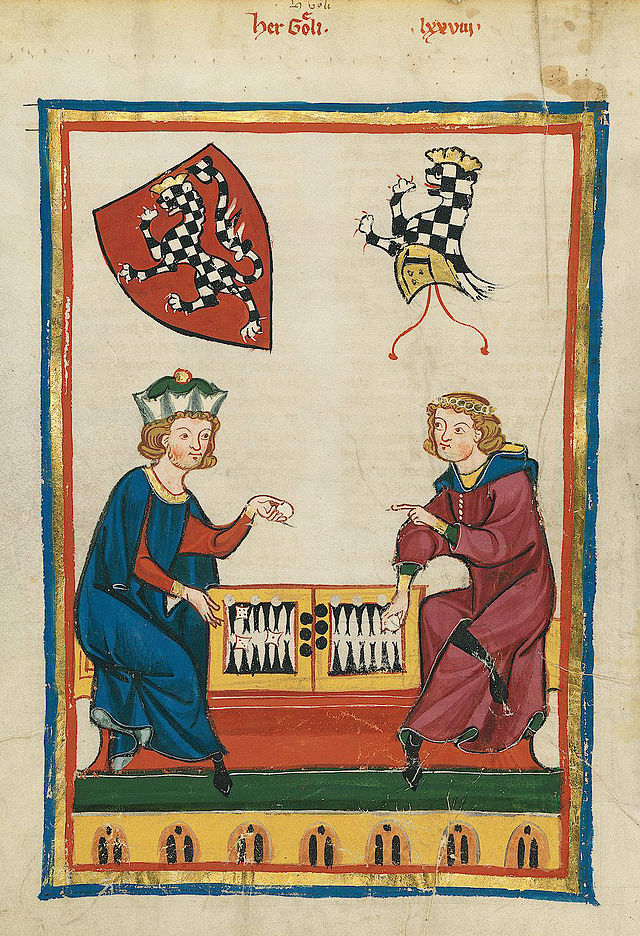

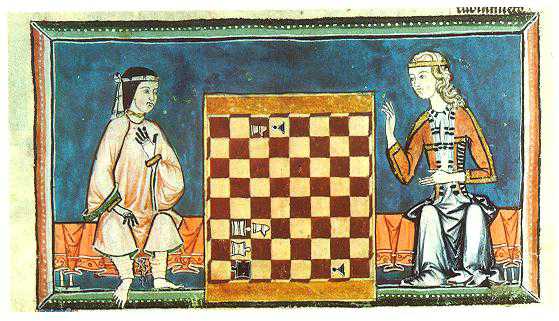

![The Carmina Burana is a collection of songs, often satirical, likely composed by rebellious Goliards [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goliard]. It contains Latin, German, and French, in two hands writing c. 1230. Here, accompanying a song about an imaginary order of lazy, gluttonous, game-playing clerics, a group of men play a backgammon-type game. Chess is also depicted.](https://medievalfragments.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/carmina-burana.jpg?w=640&h=384)