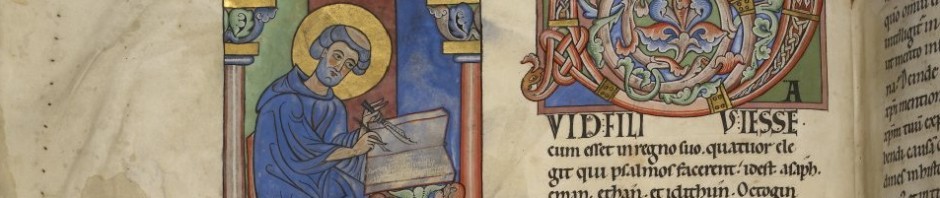

This week, while playing with the iPhone app for e-codices, the Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland, I paid an online visit to one of my favourite manuscripts, the Cantatorium of St Gall (Sankt Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek Cod. Sang. 359):

Pages 24 and 25 of Cod. Sang. 359. (N.B. St Gall’s manuscripts are paginated, not foliated.)

Photo © 2013 e-codices.

A ‘cantatorium’ is a book that contains the gradual and alleluia chants that a soloist would perform during the Mass. Amalarius of Metz (writing before 850 AD) comments in his Liber officialis that the cantor (or ‘soloist’) holds the cantatorium in his hands at the ambo (or ‘lectern’) although he does not need it to perform his duties, and that the book is bound in ivory plaques.

But what is so special about Cod. Sang. 359? Besides the fact that very few ‘independent’ cantatoria survive today (over time these books were gradually combined with other chant and liturgical books), Cod. Sang. 359 is the earliest complete neumed manuscript.

It is possible to see some of these early ‘neumes’ (or ‘notes’) above the words below:

Once believed to be the autograph of Gregory the Great (it isn’t), in 1851 this manuscript became the first published facsimile of any musical manuscript.

Despite its rare survival, Cod. Sang. 359 is not especially physically unique (which is not to say it is uninteresting). It is written in a single column, in a Caroline minuscule characteristic of St Gallen, by several hands of varying skill. The text varies in size and provides enough space between the lines to add musical notation, and the words are dispersed broadly across the line to make sure the neumes will line up properly. Given the regularity of the layout and relationship between neumes and script, it is likely that the scribe also played the role of musical notator.

Consistent with Amalarius’ description, the St Gall Cantatorium is bound between sturdy wooden boards mounted with carved ivory plaques. Dating of the oak boards has confirmed that this is the original binding. The ivory panels on the front are taken from an early sixth-century Byzantine diptych, and depict the war of Dionysus against the Indians, and were apparently once in the possession of Charlemagne. Although heavy, its narrow dimensions are designed to make it easy for one person to hold in his hands, emphasizing its use by the solo cantor.

The cantatorium’s early neumes themselves have been the core of legend and controversy: where did they come from? And for what purpose? These questions will be explored in an upcoming blog post on the history of musical neumes.

To be continued…